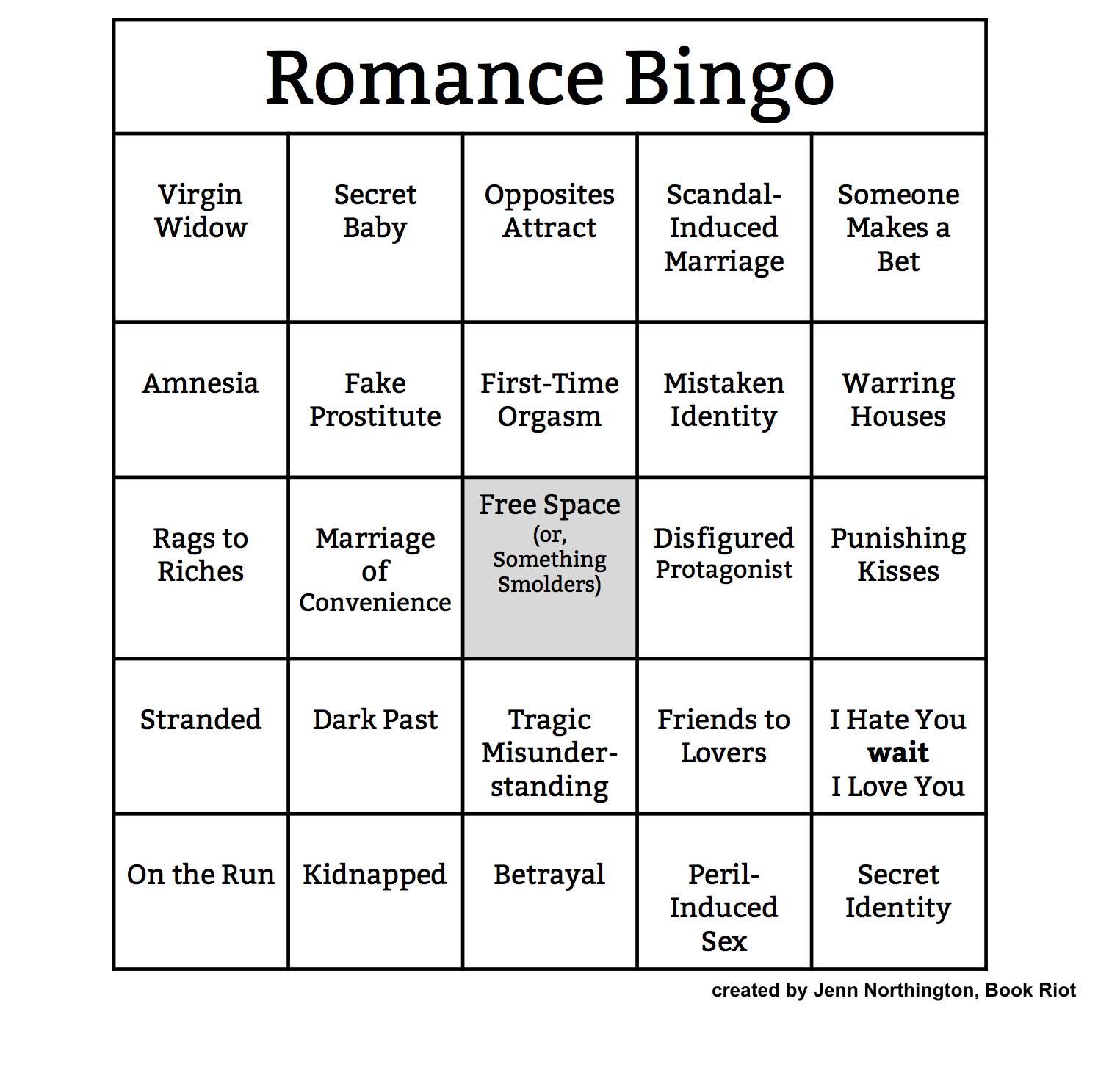

Romance Conventions: Know Them, Have Fun With Them

Romance conventions are the storylines, situations and characters that make a romance a romance. They are also sometimes called tropes or commonplaces. They are salient enough for Jenn Northington of Book Riot to make the Romance Bingo card in the title image.

Any version of the hero’s journey – a romance, for instance – bends across an arc between myth and realism.

Romance Conventions: Mythic

Toward the mythic end of the arc, the characters are larger-than-life archetypal. The situations are life-and-death. The conflict is epic.

Star Wars is a perfect example. It has the Darth Vader ‘dark father’ figure and the pure-of-heart Luke Skywalker. There’s the beautiful princess Leia and the space cowboy Han Solo. Its World War II-like conflict assumes cosmic proportions out of time and place.

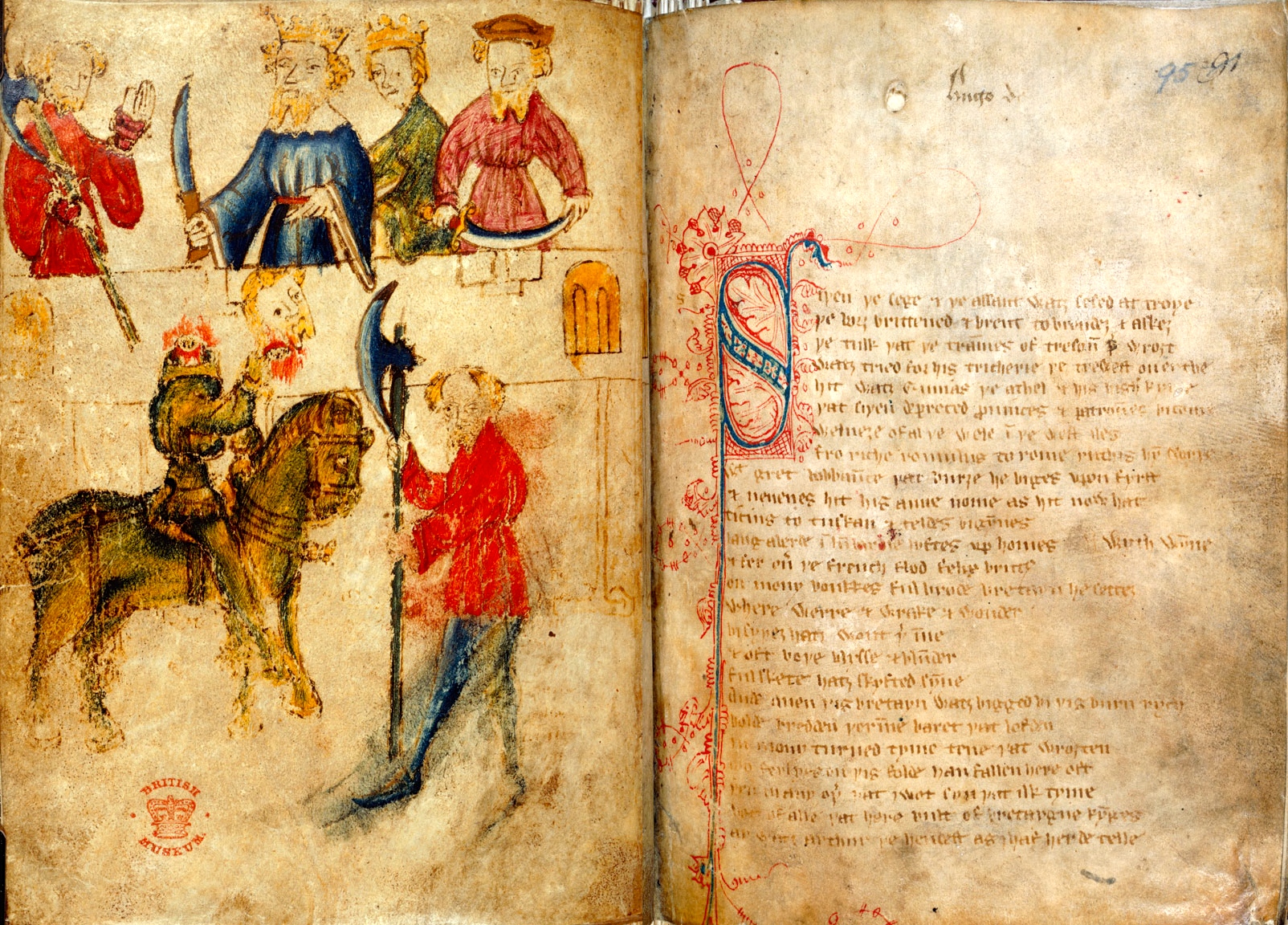

Star Wars conforms to the original, medieval version of the romance. Knights are on a quest. Damsels are in distress. Add to this magic swords, dragons to slay, and all manner of talking forest creatures. Medieval romances are like chess boards come to life. They have kings and queens and pawns and squares alternating between the black and the pure of heart.

A page from Sir Gawain and the Green Knight, a 14th-century Middle English chivalric romance

Romance Conventions: Realist

Toward the realist end of the arc, the characters are individualized and nuanced. The situations are found in daily life. The human-sized conflicts belong to specific times and places.

An excellent example is the charming Regency romance In For A Penny by Rose Lerner. The author has chosen the marriage-of-convenience convention. Her main characters are equally conventional. There’s a charming wastrel of an earl who has inherited a mountain of debt. He marries the daughter of a working-class brewer who has made a fortune the earl desperately needs. The action takes place both in London and at the earl’s estate. The conflicts are those of early 19th-century England. They involve social class distinctions, the problem of poaching, and civil unrest. We learn about the condition of workers on estates and men convicted of crimes transported to Australia.

Lerner’s characters themselves know they are in a realist romance. The heroine recommends to the hero the work of Jane Austen because “her writing is astonishingly entertaining and lifelike. There are none of the constant swoons and desperate duels amidst Gothic ruins that one sees so often in the work of other novelists.” Such a Gothic story, she says, “never taught us to know ourselves or our fellows better. It never inspired the spark of recognition that Miss Austen achieves so effortlessly. I never felt, while reading, that here was myself.”

Indeed, Lerner has created two main characters who are individual, sympathetic and recognizable. Their inner conflicts as they get to know one another (and fail, at times, to do so) in their married state are finely calibrated and believable. The tentative and halting progress they make toward establishing a bond of love is similarly believable. It’s a romance that has its feet on the ground – not in outer space.

First published in 2010

Romance Conventions: A Romance is Still a Romance

And yet vestiges of the medieval romance still cling to the modern realist romance. We speak of the characters in the archetypal roles of heroes and heroines and villains. By contrast, so-called literary fiction has protagonists and antagonists or anti-heroes. And the modern realist romance is still Quest-driven, the Holy Grail being that of True Love. Again by contrast, the characters in so-called literary fiction may do nothing and go nowhere. Take, for example, Samuel Beckett’s Waiting for Godot.

The overlap between the medieval mythic and modern realist romance (whether historical or contemporary) causes confusion to critics. Non-readers of romance and the literary establishment tend to misunderstand and underestimate this narrative form. To them the stories all seem the same, but then again they don’t. The narrative structure seems both clear and hazy.

Romance Conventions: Where Do You Stand?

To the insider the overlap explains both the choices romance writers make and their readers’ preferences.

I have a strong preference for the realist end of the arc. Nevertheless, I recognize that many talented and successful authors position themselves more in the middle. Their characters tend toward archetypes. Their fiery redhead, brainy brunette, or perky blonde would be labeled by outsiders as stock. Some characters are even anachronistic. Many a proto-feminist duke inhabits a Regency romance. The conflicts, if they’re outsized, are likely be light and frothy. And readers love their stories precisely for these qualities.

Know where you stand. And wherever you stand, have fun with the conventions!

See: All My Romance Blogs

Want to write a romance novel of your own? My complete guide to writing a book is a great place to begin.

Categorised in: Love, Writing, Writing Inspiration, Writing Romance, Writing Tips

This post was written by Julie Tetel Andresen

You may also like these stories:

- google+

- comment