Secondary Characters: Five Tips for Creating Them

Main characters are the prime movers of your story. Their goals and motivations fuel the plot. Secondary characters are there to provide support for the main action, to generate a subplot, and/or to help develop thematic material.

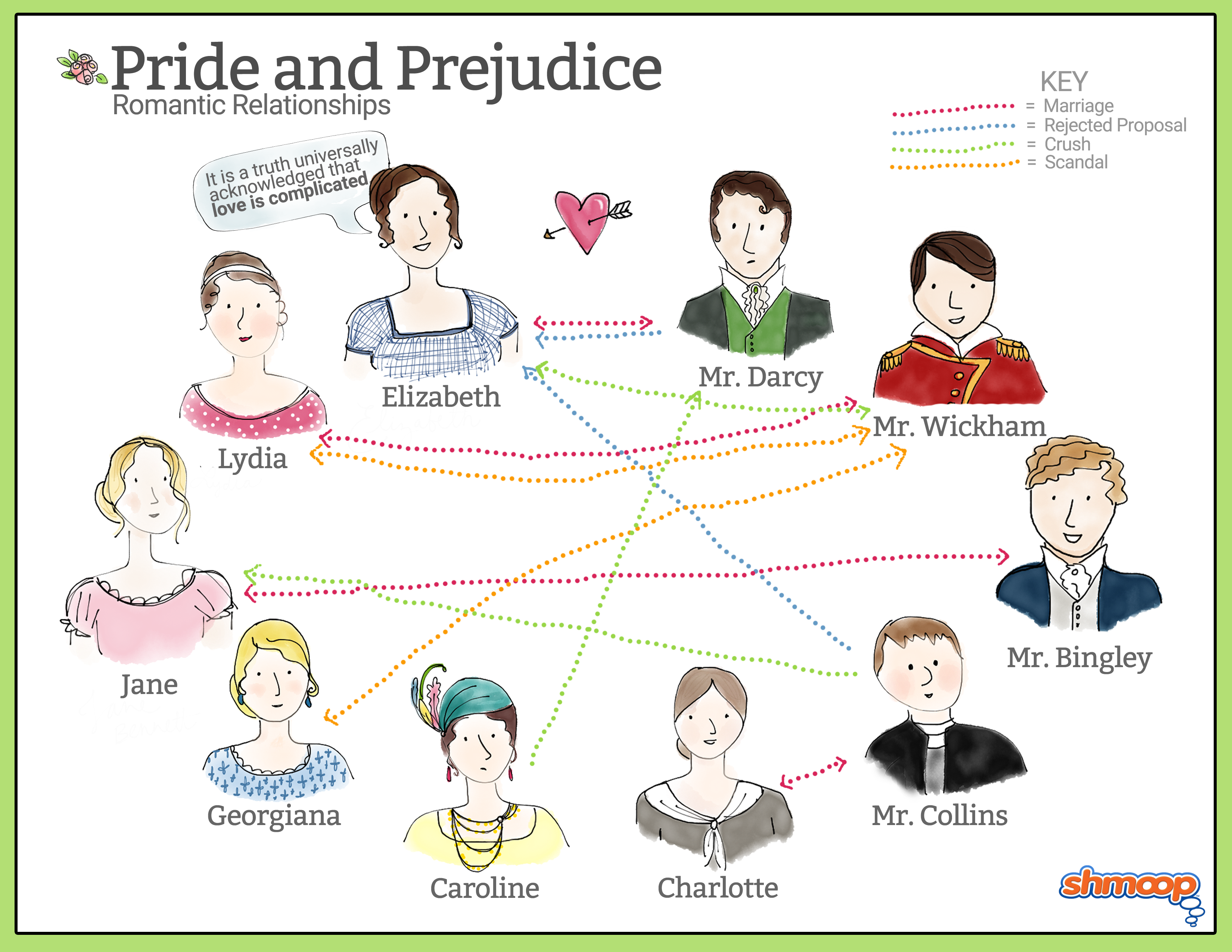

In Pride and Prejudice, Elizabeth Bennett and Mr. Darcy are the main characters. The secondary characters are: Jane Bennett, Mr. Bingley, Mr. Collins and Mr. Wickham.

The title image also includes Elizabeth’s friend Charlotte, Elizabeth’s sister Lydia, Mr. Bingley’s sister Caroline, and Mr. Darcy’s sister Georgiana. These last four I consider to be more minor characters. They are enmeshed in the plot but they figure into it more as consequences of others’ actions rather than causes.

You, the author, love your main characters. Here are some tips to spread a little love to your second bananas.

Secondary Characters: Tip #1

All characters think they’re the main character in their own novel.

Yes, in your story, the secondary characters exist in function of your main character(s). However, in and of themselves these guys are fully formed individuals with characteristic thoughts, goals and actions. You need to know them in their three-dimensional individuality and not just as they relate to your main characters.

As your story develops you necessarily won’t get to know your secondary characters as well as you do your main characters, because you won’t be spending as much time with them. Nevertheless, many a secondary character has grabbed an author’s imagination and becomes the main character in a subsequent book. If the author (or, then, reader) wants to get to know this character better, it’s a sure sign of a good secondary character!

Secondary Characters: Tip #2

Your cast of characters makes an ensemble.

Think: Friends, Modern Family, SNL, any good improv troupe. It’s the right mix of ingredients that makes the loaf. Although I’m not a staunch watcher of Modern Family I’ve seen enough episodes to identify Cameron as the yeast that makes the dough rise (for me, at least). You can make your own assessments of what the other characters bring to the batter.

I won’t extend the obvious recipe analogy farther than to say that you really need to know what kind of story you’re baking. Does it have nuts, and if so what kind? How much sugar? How much salt? Is it death by chocolate?

You flavor your story with your secondary characters accordingly.

Secondary Characters: Tip #3

Identify yourself in your story.

I don’t know how other writers work, but I never make myself the main character. If I do consciously insert (some part of) myself into a character, it’s as a friend, a mischief-maker or some kind of artist – and nothing prevents me-the-character from being all three at once.

Here’s the thing: You might already be in your story without quite knowing it. You, the straight female author, have created a gay guy but you don’t immediately see yourself in him. Look again. It’s the character’s point of view that might be yours.

You’re likely in your story somewhere. You might be in it everywhere, but for the sake of your story choose one secondary character you most want to identify with. You’ll bring clarity and confidence to the process of developing him or her.

Secondary Characters: Tip #4

Take care with your foils.

Foils are there to provide contrasts to the main characters.

Back to Pride and Prejudice. I chose Mr. Collins and Mr. Wickham as one of the four secondary characters because they are integral to the thematics of Austin’s marriage plot. Pompous prosy Mr. Collins lies at one end of the husband spectrum. The seemingly charming but ultimately caddish Mr. Wickham lies at the other. Mr. Darcy is poised perfectly in the middle.

Similarly, Jane Bennett and Mr. Bingley, with their light and untroubled love for one another (although trouble befalls them through the actions of Mr. Darcy), put into relief Elizabeth’s and Darcy’s love which is darkened and troubled by, well, gee, pride and prejudice.

Secondary Characters: Tip #5

Avoid the Greek chorus.

A Greek chorus is a non-individualized group of performers who comment with a collective voice on the dramatic action. Greek choruses are appropriate for ancient Greek drama and Thornton Wilder’s Our Town but not for modern novels.

I’ve run into too many romances lately where a character acts as a Greek chorus by having only one function. It’s either a sex-positive gal pal who nearly chants to the heroine “You need to get laid, girl” or a gay co-worker or friend who consistently comments on the hotness of the hero.

They aren’t secondary characters. They’re caricatures. And there’s only one adjective to describe their creation: lazy.

C’mon, fellow authors. We can do better!

See: All My Writing Tips

Categorised in: Love, Writing, Writing Inspiration, Writing Tips

This post was written by Julie Tetel Andresen

You may also like these stories:

- google+

- comment