Social Change: The Role of Women

For March, which is Women’s Month. The topic is social change.

Sociolinguist William Labov has observed: “While most language forms are stable and customary; a few rapidly changing variables may be closely compared to fashion. Change and diffusion of fashions – in clothing, cosmetics – appears to be closer to linguistic change and diffusion than any other form of behavior.”

When we think of clothing and cosmetics, we tend to think of women. As it turns out, women are leaders of social change in at least three areas:

Women Lead Social Change in Clothing

This fashion timeline shows a fairly dramatic shift in women’s clothing over a 90-year period.

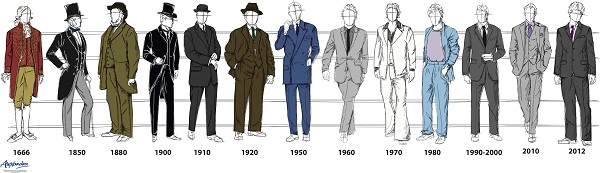

Here’s a fashion timeline for men over a 300+-year period. Not a whole lot has happened in terms of the men’s business suit:

In non-business-as-usual situations, we find New York Jets Mark Sanchez wearing a hair item formerly worn only by women, namely a headband:

and Hollywood A-listers sporting a hairstyle formerly worn only by women, namely a (man) bun:

Women Lead Social Change in Names

According to linguist Geoffrey Nunberg, men’s names are like men’s ties: there are only about six of them.

5 most popular in 1925: Robert, John, William, James, and Charles

5 most popular in 1950: Robert, Michael, James, John, and David

5 most popular in 1970: Michael, Robert, David, James, and John

Only beginning in the ‘80s did boys’ names start to bend to the winds of fashion.

5 most popular in 1982: Michael, Christopher, Matthew, Joshua, and David and Jason (the latter did not even make the top 50 ten years earlier)

Now compare with women’s names:

5 most popular in 1925: Mary, Barbara, Dorothy, Betty, and Ruth

5 most popular in 1950: Mary, Linda, Patricia, Susan, and Deborah

5 most popular in 1970: Michelle, Jennifer, Kimberly, Lisa, and Tracy (Mary at #15)

5 most popular in 1982: Jennifer, Sarah, Nicole, Jessica, and Katherine (Mary at #31, behind Megan, Erin, and Crystal)

These days both boys’ and girls’ names rapidly change from year to year. Girls’ names still remain more innovative. Dakota and Taylor come to mind, now almost standard.

Let’s factor in ethnicity. Harvard sociologist Stanley Lieberson’s data on African-American choices of names from emancipation to the present shows that freed slaves chose names favored among whites, while whites in the South changed their naming practices to try to distance themselves from the freedmen.

Today’s gap between white and black names reflects many sociopolitical forces, e.g. Black pride and conversion to Islam. Nevertheless, the pattern of greater “play” in the range of girls’ names is similar in both white and black communities.

Women Lead Social Change in Phonetic Change

Back to Labov. His studies of American English show the leaders of phonetic change to be female members of the highest status local group, upwardly mobile, with dense network connections within the local neighborhood, but an even wider variety of social contacts beyond the local area.

The vast majority of language learners acquire their first language in close contact with a female caretaker, not a male. Given this, female-dominated sound change seems to be a symbolic claim to female identity.

Note: See my blog Vocal Fry/Creaky Voice.

At the outset, girls and young women will advance the change begun by their mothers. Males, on the other hand, will not participate in the change but remain at the base level they acquired from their mothers.

It won’t be until the third generation that the differences between males and female begin to shrink with respect to a particular sound change.

The phenomenon does not seem to be restricted to American English.

A phonetic change is currently afoot in Buenos Aires Spanish and involves the devoicing (no vibration of the vocal chords) of the sound zh, as in calle and llame. This graph shows that young women are devoicing at a faster rate with 9-year-old girls the most advanced, while 15-year-old boys devoice at the rate of 36 – 55-year-old women, namely the age range of their mothers.

Labov further observes what he calls a gender paradox: “Women conform more closely than men to sociolinguistic norms that are overtly prescribed, but conform less than men when they are not.” That is, women are more likely to uphold well-known speaking norms and to avoid salient stigmatized variants, but they are likely to lead change when the variables are less noticeable.

This paradox is by no means universal.

Still, the phenomenon in the context of the U.S. is intriguing. I can’t help but think that changing hemlines, innovative baby girl names, and phonetic forwardness are part and parcel of changes in women’s social, economic and political power throughout the 20th and 21st centuries.

Categorised in: Thoughts

This post was written by Julie Tetel Andresen

You may also like these stories:

- google+

- comment